Occupational Licensing

In 2011, Nevada lawmakers passed legislation that made it a criminal offense to practice music therapy without a license.1

According to the statutory language, “music therapy” is defined as the “clinical use of music interventions … to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship.” These music interventions “may include, without limitation, music improvisation, receptive music listening, song writing, lyric discussion, music and imagery, music performance, learning through music and movement to music.”

In other words, lawmakers made it a criminal offense to teach someone how to dance, write songs, or even listen to music unless the instructor has paid fees and obtained a state-sanctioned license.

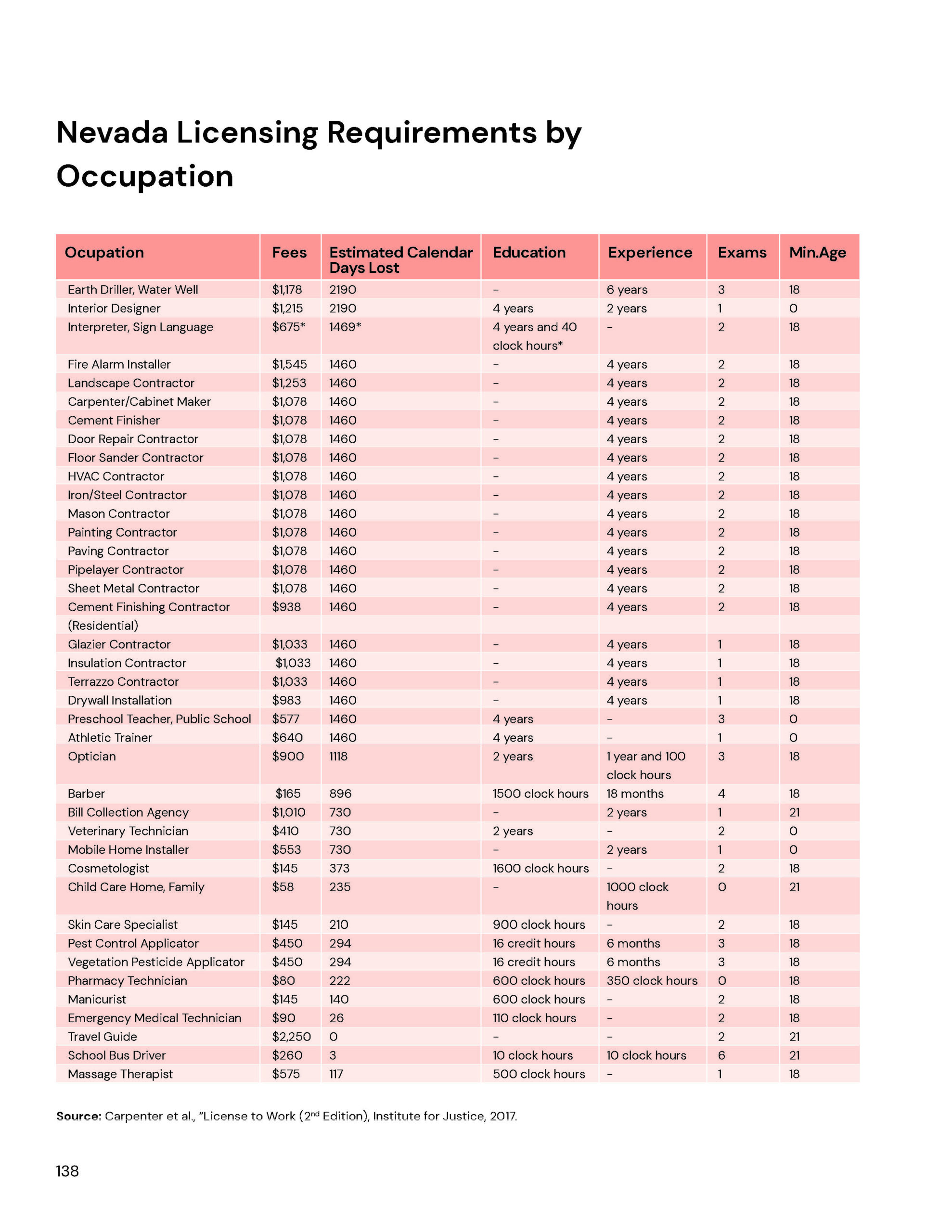

Indeed, for more than 70 different occupations in Nevada, lawmakers have required providers to pay regular fees to a state-sanctioned licensing board, or face potential criminal charges. In many of these cases, it is clear such legislation is not in the public interest.

Key Points

Nevada imposes some of the most restrictive licensing requirements in America. According to a 2017 state-by-state analysis of occupational licensing laws:

Nevada is the second worst state in the nation for occupational licensing of lower-income occupations. Licensing 75 of the 102 [occupations] studied here, Nevada is more broadly and onerously licensed than all but one other state. Nevada also has the second most burdensome licensing laws, requiring, on average, $704 in fees, 861 days – more than two years – of education and experience, and around two exams.2

A 2022 update to that analysis confirms that Nevada’s licensing “[b]urden remained the second worst and [its] combined rank remained the worst” among the states.3

Occupational licensing is often designed by industry insiders to exclude competition. In many cases, occupational licensing bills are heavily influenced by industry insiders who want to forcibly exclude competition from the marketplace. Once lawmakers create an occupational licensing board, the members who populate that board are typically industry insiders, as well. This ensures an obvious conflict of interest, empowering board members to decide who may legally compete with them.

Statutory language is ambiguous. The statutory language providing for many occupational licenses fails to clearly limit the law’s coverage to only “for profit” providers. For instance, NRS Chapter 640C appears to make it a criminal offense for an individual to give his or her spouse a massage without a state-sanctioned license.

Many occupations subject to licensing present no meaningful danger of physical harm. In Nevada, individuals cannot cut hair, apply makeup, give advice on interior design, or provide landscaping services without first paying a fee and obtaining permission from their would-be competitors. The transparent intention behind these obstacles is to dissuade talented new individuals from entering these markets.

Occupational licensing is not “consumer protection.” The demand for an individual’s services on the open marketplace is only as strong as that individual’s reputation for quality. Interior designers who dispense poor advice, for instance, are unlikely to remain in that industry for an extended time. Although advocates of occupational licensing claim to be intent on protecting consumers from poor quality, their political methods are less adequate for this task than simple market forces.

Recommendations

Restrict occupational licensing to professions that meet a narrow definition for “substantial risk of physical harm.” Lawmakers should immediately repeal all occupational licensing requirements for professions that do not pose a substantial risk of physical harm to consumers when the occupation is not performed by a trained professional. Assembly Bill 269 was introduced during the 2015 session to accomplish this task, but it failed to receive a committee hearing.4

1 Nevada Legislature, 76th Session, Senate Bill 190.

2 Dick Carpenter et al., “License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing (2nd Edition),” Institute for Justice, November 2017.

3 Lisa Knepper el al., “License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing (3rd Edition),” Institute for Justice, November 2022.

4 Nevada Legislature, 78th Session, Assembly Bill 269.