Medicaid Spending & the ACA

Medicaid is a state-run program that provides health care services to poor, elderly and disabled populations.

States are not obliged to operate Medicaid programs, but Congress offers matching grants to states that do. The grants are apportioned according to a formula that is based on a state’s median, per-capita income level. Federal funding is guaranteed to cover 50% of costs, and, in FY24, Mississippi receives the highest reimbursement rate, at 77.27% percent.

The federal contribution rate is called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage, or FMAP. For FY 2024, Nevada’s FMAP is 62.24%. This means that Nevada taxpayers are directly liable for only 39% of the program’s costs, although indirectly they finance the remainder in their capacity as federal taxpayers.

Notwithstanding the federal contributions, Medicaid imposes a large and growing liability on the state budget. Nationwide, Medicaid spending has quickly grown to become the largest item in state budgets.1

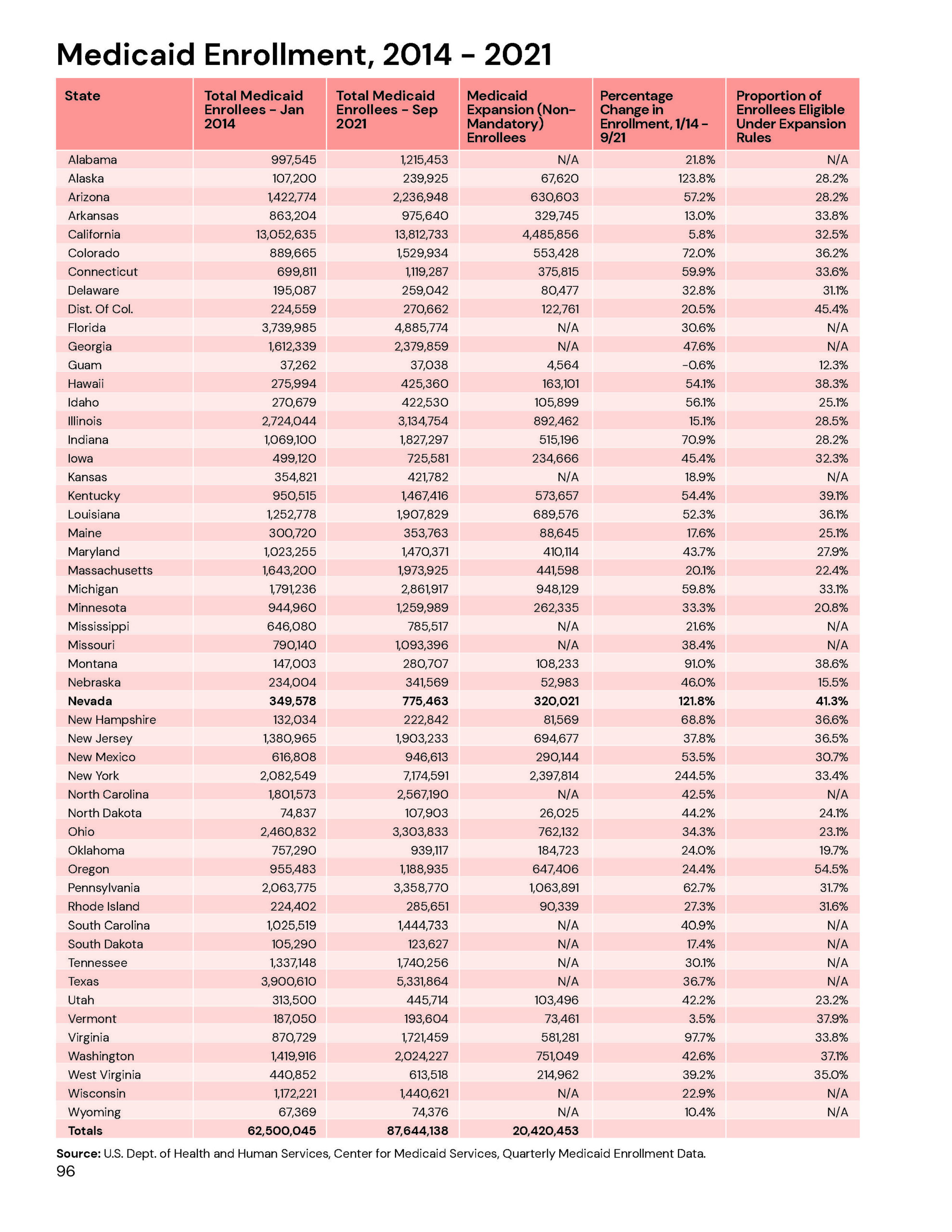

Nevada will pay $2.427 billion out of the state general fund to support Medicaid during the 2023-2025 budget cycle, a 124% increase over the past decade.2 Eligibility rules were expanded in 2013 to include single, childless adults and all other individuals earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level, which has driven enrollment growth. Nevada’s Medicaid costs have grown proportionately.

Key Points

Medicaid spending was already on an unsustainable trajectory prior to eligibility expansion. Nevada Medicaid spending has risen faster than state economic output. If left unchecked, this means Medicaid spending would eventually crowd out all other government functions in Nevada, including public safety and schools.

Eligibility expansion has imposed much higher Medicaid costs on Nevada taxpayers. The federal Affordable Care Act was designed to expand medical coverage to the uninsured by pushing more individuals into state Medicaid programs. It does this in two ways.

First, it offered financial incentives for states to expand eligibility, bringing 239,000 additional enrollees into Nevada Medicaid by 2014. For the first three years, state taxpayers did not directly pay for care received by these new enrollees as it was paid by federal taxpayers. Beginning FY 2017, however, federal contributions began to decline. By FY 2023, the enhanced FMAP for the newly eligible population fell to 73.86% percent.

Second, the individual mandate included in the ACA induced about 65,000 new enrollments by individuals who were eligible under the old rules, but, for whatever reason, elected not to enroll. For these enrollees, only the standard FMAP applied – meaning that state taxpayers immediately began facing a new liability.

Enrollment growth has outpaced early projections, which forecast 802,000 by 2023.3 Enrollment reached 904,158 by July 2022, representing more than 28% percent of the state population.

Recommendations

Implement a comprehensive re-design of Medicaid. If Nevada policymakers are intent on retaining the eligibility expansion they agreed to in 2013 pursuant to the ACA, then the imperative of a Medicaid redesign to improve the program’s cost-effectiveness grows even more pronounced.

Enrollment growth over the next decade poses an insurmountable challenge for Nevada’s budget and may force major spending reductions in other areas while providing only substandard health care to thousands of Nevada citizens. Fundamental restructuring of the state’s Medicaid delivery systems is imperative. Options for a Medicaid redesign are discussed in the Medicaid Reform section.

1 National Association of State Budget Officers, “The Fiscal Survey of the States,” 2015.

2 Nevada Legislature, Legislative Counsel Bureau, “Appropriations Reports.”

3 Jagadeesh Gokhale et al., “The Impact of ObamaCare on Nevada’s Medicaid Spending,” Nevada Policy Research Institute policy study, 2011.