PERS: Assesing the Liability

Official financial statements from the Nevada Public Employees’ Retirement System indicate that, at the close of FY 2021, the system held $58.3 billion in assets versus $76.6 billion in liabilities. This ratio would mean that PERS has a funding ratio of 76.2% and an unfunded liability of $18.3 billion.1

However, the actuarial accounting method used by PERS and other public-sector pension programs is at odds with the generally accepted method that private companies use to value future liabilities. The PERS method glosses over most of the system’s unfunded liability by failing to account for risk.

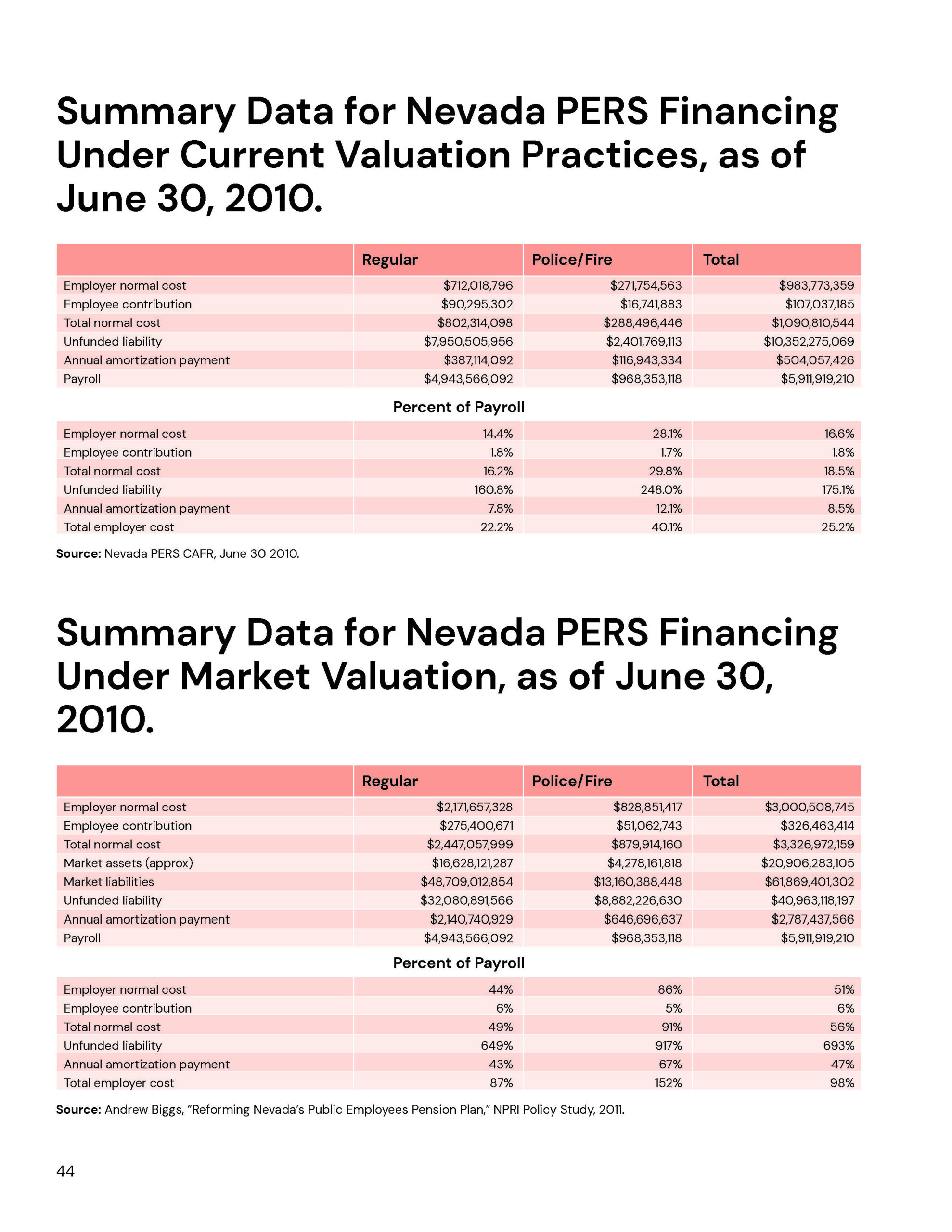

If PERS accounted for risk within its investment portfolio as private-sector pensions and other entities must do, it would become clear that PERS’ official liability estimates are dramatically understated. The true value of the system’s unfunded liability at the close of FY 2010, for example, was about $41.0 billion while PERS only reported an unfunded liability of $10.4 billion.2

Key Points

Actuarial accounting conflates assets and liabilities. PERS accounting methods discount the value of expected future liabilities by the system’s assumed annual rate of return on investments (7.25%) to calculate the present value of liabilities. However, finance professionals generally agree that liabilities should be calculated independently of assets. The future value of financial securities are uncertain, while liabilities can be calculated with exactitude.

PERS does not account for risk in its investment portfolio. If retirement benefits promised to government workers in the Silver State are regarded as a zero-risk guarantee, then PERS accounting should backstop these benefits with zero-risk investments, or at least investments that are price-adjusted for risk.

The retirement system’s current accounting practices treat high-risk investments the same as low-risk investments. This failure to account for the pricing of risk forces a contingent liability onto taxpayers when risky investments do not achieve the expected yield.

PERS accounting encourages risky behavior. PERS accounting practices allow administrators to incorporate illusory gains into the balance sheet immediately – despite the fact that those gains might never actually be realized in the marketplace. Administrators then must try to realize those gains and may be encouraged to purchase risky assets to achieve the return they need.

PERS expected rate of return has not always been realistic. PERS assumes that it can receive a 7.25% return on investments every year into perpetuity. However, in the decade between 2014-2023, the system achieved this return six times. When the targeted return isn’t achieved PERS must reverse gains it has already effectively recognized, leading to a deterioration of the balance sheet.

Depending on the future trajectory of Federal Reserve target rates, PERS may be unlikely to again see the higher return rates earned in decades past. The zero-risk baseline for earnings – 10-year federal Treasury bond yields – has fallen from the 8-plus percentage point range of the 1980s to around 5.3% today.

Therefore, the rate of return assumed by PERS should be adjusted downward to reflect the lower yield of today’s zero-risk or risk-adjusted assets. This will re-incorporate the contingent liability and reveal the true size of the system’s unfunded liability – estimated at $41.0 billion as of FY 2010.3

Recommendations

Require PERS to incorporate a market-based accounting approach. If policymakers and taxpayers want to uphold the promises made to public employees in Nevada, they first need to have a clear understanding of what those promises entail. Public pension systems are recommended to follow GASB standards, but can elect to follow more rigorous FASB standards.

Federal Reserve Board economists, along with many others, have urged this shift in accounting practices for public pension systems.4

1 Nevada PERS, 2023 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

(Differences due to rounding).

2 Andrew Biggs, “Reforming Nevada’s Public Employees Pension Plan,” NPRI policy study, 2011.

3 Ibid.

4 See, e.g., Donald Kohn, “Statement at the National Conference on Public Employee Retirement Systems Annual Conference,” May 20, 2008; David Wilcox, “Testimony before the Public Interest Committee Forum sponsored by the American Academy of Actuaries,” September 4, 2008.